Advocates for Michigan foster youth hope education reforms will pass this year

By Hannah Dellinger | January 18, 2024, 11:30am EST

When Christian Goode transferred from a traditional high school to Lakeside Academy, a state-licensed residential foster care facility near Kalamazoo, some of his academic records never made it over.

As a result, he had to repeat an entire year of classes, and redo school work he had already completed.

“At times, I didn’t want to do it, because I had already done it,” Goode said of the work. “It felt like I was forgotten and no one cared.”

Goode is now 21 — years past high school and living in Van Buren Township. But the holes in Michigan’s foster care system that disrupted his education persist today, and they continue to create turmoil for thousands of students in foster care.

As reported by NBC in 2022, many students describe having to repeat years of school due to lost academic records. Some say they were placed in residential facilities that failed to give them an education that met state graduation requirements. Others said they missed weeks or months of school while waiting to be enrolled after moving to a foster-care facility.

Their experiences are now inspiring efforts in the Michigan Legislature to ensure that students in foster care get more of the education they deserve.

“These are young people who have already been dealt a lot of trauma,” said State Rep. Stephanie Young, a Democrat from Detroit. “The very minimum we can do is ensure they get the best education they can.”

Three bills introduced last year by Young passed the Michigan House in November. Young said she is pushing for the legislation to move quickly through a hearing in the Senate Housing and Human Services Committee and for a vote in the Senate. She says the bills have bipartisan support.

One of the bills would require that residential facilities enroll students in school within five days of placement, and that they provide an education that meets the state’s graduation requirements. Another bill would give the Michigan Department of Education responsibility for overseeing the facilities’ educational programs and enforcing compliance.

The third bill would require the MDE and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services to keep better records on the number of children in foster care, where they are, and how they’re progressing in their education.

The state has an estimated 10,000 kids in foster care, but the total number is unknown because many go uncounted in the current system, advocates say. For example, people ages 18 to 23 who are still eligible to receive state services are not included in that count.

Michigan foster youth have a high school graduation rate of about 40% – lagging about 40 percentage points behind the state’s overall graduation rate. That figure doesn’t give a clear picture either, because it doesn’t include youth who drop out or complete high school in residential facilities.

“This problem has existed for years, and we’ve finally decided to come up with a solution,” said Young. “I don’t foresee any major obstacles in moving this thing forward.”

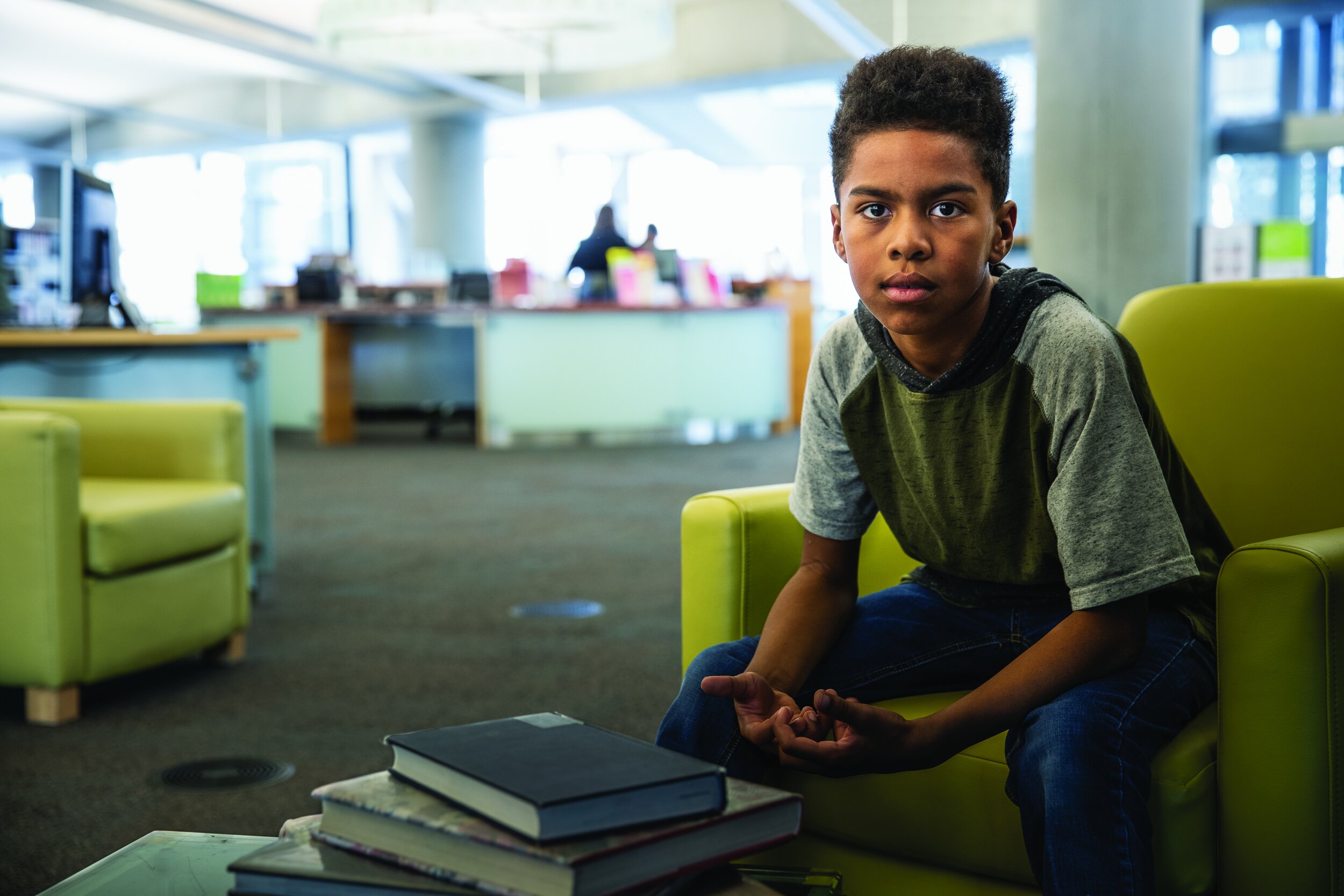

A group of foster youth and advocates spoke at the Dec. 12 Michigan State Board of Education meeting to ask the board to support a package of bills that would reform the way the state oversees education for kids in foster care. (Image courtesy of Park West)

Inadequate record-keeping adds to challenges for youth in foster care

Christian Randle entered the foster care system at age 11, when he said he was abandoned by his mother. He thought he was excelling in his school work for years, and worked hard to fulfill the promise he made to himself that he would graduate high school.

But when he left a residential facility and tried to enroll in a traditional community high school two years ago, he found out there was no record of him attending nearly three years of high school. In fact, Michigan has no centralized electronic system to track foster youth and their educational records.

“Through all that stress and trauma going on inside of that foster care facility, the one thing I was happy about coming out of it was my schooling,” Randle, now an 18-year-old senior at an online school, said in January. “And that was taken away from me.”

“I felt defeated and like I had to restart everything,” he said through tears. “To me, it felt like my life was over.”

The inability to access records also makes it impossible for traditional public schools to identify students who are in foster care, which can deprive those children of resources they need or their rights under federal education law.

For example, schools can’t fulfill the federal Title I requirement to engage with students’ families if they can’t identify who holds a foster youth’s parental rights. Neither can they comply with the federal 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act’s assurance of transportation for foster youth if they can’t identify which students are in foster care.

“They are invisible in schools,” said Saba Gebrai, program director at Park West, a Michigan nonprofit that supports foster youth. “Under the federal law, they have all these protections, but we can’t protect and serve them if we don’t know who they are.”

Because schools can’t see the youths’ case files, administrators can’t identify who has their parental rights. Biological parents, caregivers, and students old enough to hold their own parental rights are routinely denied access to the educational records they are legally entitled to.

Carlos Correa, a former foster youth who spoke about his experience to the Michigan State Board of Education in December, said he regularly struggled to get absences excused when he was in high school.

“They kept insisting that I get permission from my parents to attend my doctors appointments,” he said.

Education for foster youth lacks consistency

Beyond the record-keeping, it’s the quality of education that concerns many advocates for foster youth.

When kids move from one facility to another, often in the middle of a school year, there is no continuity in their curriculum, said Gebrai. The assessments they take to determine what classes or grade levels they should be in vary from facility to facility.

Residential facilities, many operated by private companies, can decide on their own what students are taught.

“Graduation and high school diplomas are not mentioned in the contracts that these facilities have,” said Gebrai. “Each facility is creating its own idea of what school is and what assessments to give, and they are not in communication with each other.”

Many youth who live in the facilities describe being placed in classrooms packed with kids of all ages and grade levels. They say there is often only one instructor or facility staff member overseeing large numbers of students. Some say they are instructed entirely online, and others say they are assigned packets to complete as lessons without instruction from a teacher.

“I was in a place for like one month without receiving education because of constant fights,” said Correa of a residential facility he was placed in.

Existing state laws require parents or facilities only to provide youth with “timely” enrollment in school. That vague language often leads to weeks of missed school for kids moving around in the system, advocates say.

Young said the explicit five-day deadline in the legislation she introduced would clear that up.

Gebrai and other advocates argued for the bill to mandate “immediate” placement, but Young argued for some flexibility. “Kids might be dealing with the trauma of being removed from their house and the only school they knew,” said Young. “Going to a new school the very next day, that’s traumatic. I get that there needs to be some wiggle room.”

According to a fiscal impact analysis of the bills, the laws would cost the state around $600,000 to hire three full-time staff members in the MDE to implement the proposed new requirements.

The residential facilities may contract with public schools to provide curriculum, the analysis says. The school aid budget already allocates $10.5 million to reimburse districts for on-site education for youth.

Foster youth see an opportunity for change

Goode, the former Lakeside Academy student, ultimately got his high school diploma there, and plans to go back to the University of Michigan-Flint in the fall. But he feels he missed out on a “normal” high school experience and childhood.

“I’ve never been to a homecoming dance or prom,” he said. “I’ve never experienced a high school science fair. A lot of things I grew up without and I sat on the outside of it. I can’t change that now.”

But he and Randle see Young’s bills as hope that things can change for other youth in foster care.

Randle, who lives on his own in Southfield and works several jobs to support himself and his cat, hopes to complete high school this year. His dream is to be the first in his family to attend college and to eventually have a career helping foster youth.

He says the changes in the law are long overdue.

“It’s the bare minimum that they can do, because they haven’t been doing anything for years,” said Randle. “It shouldn’t even have taken this long to pass the bills. Just the fact that it’s had to take this long shows a lot about how kids in foster care are treated.”

Hannah Dellinger covers K-12 education and state education policy for Chalkbeat Detroit. You can reach her at hdellinger@chalkbeat.org.